— By Ron Jenkins, a visiting professor at Yale Divinity School who has taught ISM courses on prison and the arts since 2015. Ron was also an ISM fellow from 2022-23.

“I had a life-sentence and I didn’t think I was coming home, sometimes I would feel like my life was over. I would go to the prison chapel, get on the piano, and just sing. That would be my way of talking to God.”

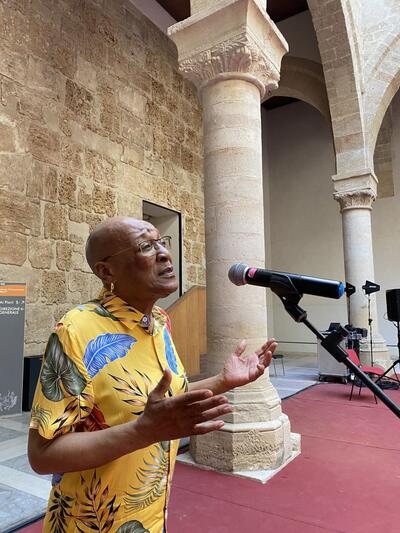

Naomi Wilson spoke these words to an audience in a seventeenth-century Italian courtyard as a prelude to singing an African-American spiritual that expressed the essence of her prayers during the thirty-seven years she spent behind bars: “Oh, Freedom!”

It was a song she has sung to standing ovations in many venues, including in Yale Divinity School’s Marquand Chapel, where she collaborates with other formerly incarcerated individuals in a course that helps students use Gospel music, rap poetry, and true stories to raise awareness about the impact of mass incarceration on millions of American families.

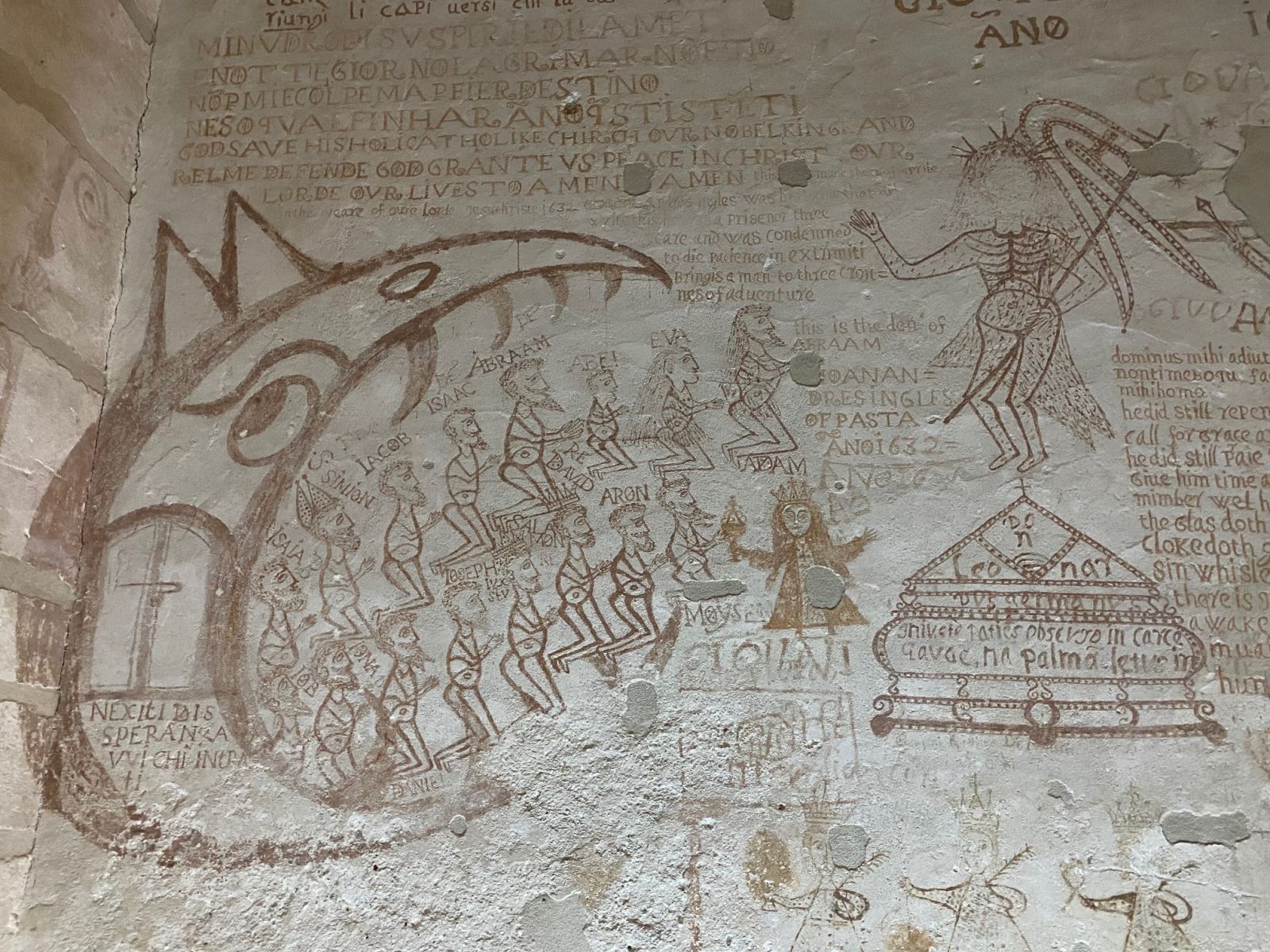

Christ leads souls out of Dante’s hell-mouth: 17th century graffiti drawn on Palermo dungeon walls by prisoners of the Inquisition. (Photo: Ron Jenkins)

Her Italian performance was from a play that grew out of this Institute of Sacred Music (ISM) course and was featured in Sicily’s 2023 music festival, “Palermo Classico.” Entitled “Surviving Troubled Waters: From Prison to Freedom Through Music,” the play also featured BL Shirelle, a poet who has transformed her life experiences, before, during, and after prison, into propulsive rap rhythms that speak to the heart of anyone who has endured hard times. The stories and songs of Wilson and Shirelle are framed in the play by Dante’s journey from hell through purgatory to heaven in The Divine Comedy. Dinny Aletheiani weaves the scenes together with quotes from Dante’s poem and acapella renditions of sacred music that appears in each canticle: Miserere from Inferno, In Exitu Israel from Purgatory, and Regina Caeli from Paradise.

The voices of Wilson, Shirelle, and Aletheiani echoed hauntingly through the stone towers, gothic arches, and cloistered courtyards of the seventeenth century complex that also includes secret dungeons used to house prisoners of the Inquisition from 1602-1783. The records of the tortures and executions that took place during those years were destroyed by fire, but the experiences of the men imprisoned there has been preserved in the graffiti on the cell walls, which includes images of angels, saints, Virgin Mary, and Christ on the cross, along with prayers, poems, and quotes from Dante’s Inferno.

Dante himself was convicted of crimes and wrote the Divine Comedy in exile knowing he would be burned at the stake if he tried to return home. Historically his poetry has had a special appeal for incarcerated readers who include the Italian political prisoner Antonio Gramsci, the Russian dissident poet Osip Mandelstam, the concentration camp survivor Primo Levi, and the contemporary Chinese artist/activist Ai Wei Wei. Wilson and Shirelle are part of that tradition, as were the men imprisoned by the Inquisition in the castle complex who added Dante’s words to the palimpsest of poetry, prayers, and lamentations engraved in their dungeon walls. That tradition also extends to the currently and formerly incarcerated men and women who work with Wilson, Shirelle and Divinity School students in the ISM course that culminates in a performance interweaving stories about prison with sacred music and fragments from Dante’s poem.

Reflecting on the graffiti preserved on the prison walls of Palermo Shirelle observed that “the documentation that has been left behind through beautiful, painful art has provided a vital oral history of incarceration. The performance has been transformative in my mission to amplify incarcerated artists all over the world.”

Aletheiani, director of Yale’s Southeast Asian language program was deeply moved by the experience of performing with Wilson and Shirelle at a site where imprisoned priests and scholars were tortured in the seventeenth century:

“Singing Latin hymns in that historic Palazzo made their meaning come alive and allowed me to reflect on the memory of those who carved images of Regina Caeli on the walls of their cells hundreds of years ago. There is a direct correlation between the Inquisition’s torture of non-believers and the pain Naomi and BL endured in today’s prison system.”

Shirelle’s rap lyrics reinforce Aletheiani’s observation with rhymes that link her spiritual journey to questions raised by Dante about religious tolerance. Both verses resonate with the experience of men imprisoned by the Inquisition.

In the seventh sphere of heaven Dante asks about “… a man born on the shores of the Indus where there is no one to speak or read or write about Christ… his life and words are without sin… but he dies without being baptized… where is the justice that condemns him, and why is he at fault for not believing.” (Paradise, Canto 19, lines 70-79, author’s translation).

Written before she read The Divine Comedy, Shirelle’s rap seems to be in dialogue with Dante’s words, and is particularly relevant to her performance at a site where so many men were persecuted for their religious beliefs:

“So if I praise my God until I go numb

And die, then find out it was the wrong one

Am I condemned ‘cause I was speaking in the wrong tongue?”

This is only one of the many parallels between BL’s lyrics, Dante’s poem, and the prison graffiti in Palermo. The quote from Dante that the victims of the Inquisition chose to write twice on their cell walls is the one that BL, Naomi, and the Yale students always discussed in relation to incarceration: “Abandon hope, you who enter here.” The phrase’s despairing tone, however, is counteracted in Palermo by the accompanying drawing that depicts Christ leading damned souls out of the mouth of hell. That poignant image is surrounded by more graffiti in which despair is tempered with dreams of salvation. Amidst the drawings of Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows, weeping women, and auto da fe processions that preceded public executions there are also emblems of hope. A few hundred meters away from the courtyard where Naomi performed was a prison cell wall with a small banner in Latin that mirrored the hopeful theme of Naomi’s story. “Shackles and chains speak miracles.”

Photo to left: Naomi performing in the 17th-century courtyard of the Palazzo Chiaramonte complex that includes the secret prisons of the Inquisition.

Photo to left: Naomi performing in the 17th-century courtyard of the Palazzo Chiaramonte complex that includes the secret prisons of the Inquisition.

The miracle Naomi recounted in Palermo was the unexpected commutation of her conviction, initiated by Pennsylvania Lieutenant Governor (now senator) John Fetterman that overturned her life sentence and eventually made it possible for her to sing a spiritual about freedom in a setting haunted by a history of oppression. The exuberance of her performance in Italy throbbed with a power that seemed capable of exploding shackles and chains the way high notes can shatter glass.

Dante wrote that the purpose of his journey through the afterlife was “looking for freedom.” Throughout their long journeys towards freedom Wilson and Shirelle have dedicated their music to everyone impacted by prison, who, more than most, might empathize with the writings scrawled on Palermo’s dungeon walls four centuries ago:

“This is a crying place”

“You bless us with your words, but you curse us in your hearts.”

(And two words next to a crudely drawn set of prison bars)

“Free us”

Ron Jenkins is a professor of theater at Wesleyan University and a former fellow at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music from 2022-23. He teaches ISM’s “Gospel, Rap, and Social Justice” course as a visiting professor at the Yale Divinity School. He wrote the script for “Surviving Troubled Waters” based on several years of interviews with Naomi Wilson and BL Shirelle. The play’s performance at the Palermo Classico Festival was hosted by the Graffiti Art in Prison Project based at the University of Palermo with the support of the European Union’s Erasmus Project.