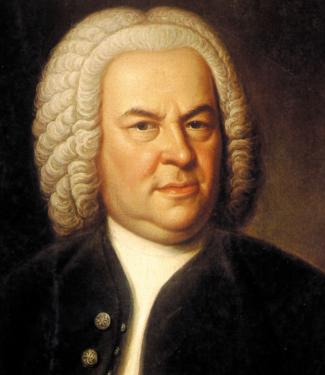

Markus Rathey: Program Notes

J.S. Bach: St. John Passion

The St. John Passion (BWV 245) was the first setting of the passion story that Johann Sebastian Bach composed after assuming the prestigious position of cantor at the Thomas Church in Leipzig. Bach had come to Leipzig in the summer of 1723; less than a year later he performed his passion on the afternoon of Good Friday, 1724.

The St. John Passion (BWV 245) was the first setting of the passion story that Johann Sebastian Bach composed after assuming the prestigious position of cantor at the Thomas Church in Leipzig. Bach had come to Leipzig in the summer of 1723; less than a year later he performed his passion on the afternoon of Good Friday, 1724.

At that time, the tradition of performing large-scale passion compositions was not well-established in Leipzig. Only during the last years of Bach’s immediate predecessor, Johann Kuhnau (1660–1722), had it become customary to perform a figural setting of the passion in the oratorio style during the Good Friday vespers.

Altogether, Johann Sebastian Bach composed five Passions, according to the estate catalogue compiled by his son Carl Philipp Emanuel: two of them are lost and one, the St. Mark Passion, exists only as a fragment. The two surviving complete works are based on the Gospels of John and Matthew. Both underwent numerous revisions; Bach reworked the compositions several times, replacing movements and changing some of the texts and the music. For the St. John Passion alone, Bach scholars have been able to reconstruct no fewer than four different versions. In the year following the original 1724 performance the piece underwent significant revisions before the boys’ choir of St. Thomas’s performed it again on Good Friday, 1725. Around 1732, and again toward the end of his life (probably around 1749), Bach made more revisions and reversed some of the changes he had made in 1725. In this performance, you will hear a version that is, in all likelihood, quite close to the first performance in 1724.

The text for Bach’s St. John Passion was not written by a single author, as was the St. Matthew Passion; rather, it is a compilation of different texts. The biblical narrative from the Gospel of John serves as a backbone for the libretto. Other texts are Protestant hymns and free poetry containing reflections on the passion story. Several of the texts of the arias are borrowed from a libretto by Barthold Heinrich Brockes (1680–1747), one of the most successful passion texts of the 18th century, known (and notorious) for its very graphic descriptions of the wounds and suffering of Jesus. Other aria texts were taken from writings by Christian Weise (1642–1708) and Christian Heinrich Postel (1658–1705).For several of the aria texts the author is unknown.

We can only speculate as to who compiled the libretto for Bach’s passion. It could be that one of the theologians in Leipzig was responsible and wrote some of the poetic texts himself. Clearer than the identities of the individual authors, however, is the function of their texts in the passion libretto set by Bach. The different text genres represent distinctive layers of time and space, and of individual and collective reflections on the passion narrative.

The heterogeneous genres stand in a complex inter-textual (and –textural) relationship.

- The biblical text provides the narrative, and is set chronologically within the span of Jesus’ lifetime.

- The arias represent an observer operating beyond time meditating on the meaning of the passion: both present at the crucifixion, and also serving as a reader of the biblical narrative who contemplates the suffering of Christ (and its meaning) from this individual perspective. In other words, the observer could be in Jerusalem or Leipzig – or in New York or New Haven, for that matter.

- Finally, the hymns represent the reaction of the Christian congregation, here and now. The hymns help to build the bridge between the narrative of the passion and the congregation; within the liturgy, they are the pieces that “belong” to congregation.

Bach’s St. John Passion shows a deep understanding of the theological and poetic layers of its text. The composition begins with a monumental choral movement, praising God as the ruler of the world. The chorus sings the word “Herr” (Lord) in emphatic chordal blocks against a multilayered instrumental accompaniment, in which the higher strings play a continuous chain of running 16th notes to create the impression of uninterrupted movement. Bach later underlays this musical idea with another that emphasizes the word “Herrscher” (ruler), which we may call the “glory-motive,” signifying the power of God. In the first measures of the opening movement, however, Bach has already introduced the idea of pain and suffering juxtaposing this “glory-motive” with stabbing, dissonant sounds in the flutes and oboes. Thus, the opening measures of Bach’s passion present the theological view of Christ’s suffering—characteristic of the Gospel of John—from the outset: the suffering and death of Christ are the very manifestation of his glory. The same musical idea, with its dissonant sonorities, recurs later in the chorus “Kreuzige” (“Crucify”).

After this musically monumental and theologically charged opening movement comes the first half of the passion setting, the narrative of Christ’s suffering from the betrayal of Judas until the denial of Peter. In 1724 (and at the other performances conducted by Bach), this first musical part was followed by a sermon of approximately one hour. Most listeners of modern performances will not notice the bipartite structure of the passion. Only the unusual hiatus of two hymn stanzas (one ending the first part and the other opening the second) marks the transition from part one to part two.

The biblical narrative of the passion is primarily set in simple, declamatory recitatives sung by the evangelist or the other soloists (the dramatis personae of the narrative). Only when a larger crowd of people is speaking, as in the overwhelming “Crucify” chorus, does the entire choir sing the biblical text. The speech-like style of the recitatives is interrupted by the soloistic arias that serve as points of repose and reflection. The relationship between the biblical text and the reflective arias can be seen in movements 8 and 9 of the passion. Movement 8 reports that Jesus, after his arrest, was followed by Simon Peter and another disciple. The subsequent aria, whose text begins with “Ich folge dir gleichfalls mit freudigen Schritten” (I follow you likewise with joyful steps), interprets the act of following from the perspective of the Christian believer. The text of this aria resembles a small-scale sermon, explaining the biblical narrative’s meaning for the individual. Bach musically depicts the idea of “following” by setting the text in a dialogue between soprano and two flutes, where one voice imitates (follows) the other.

The melodic contour that is used by Bach at the beginning of the aria movement returns later in the chorus “Sei gegrüßet, lieber Judenkönig” (We greet you, dear King of the Jews). The theological meaning of this motivic connection across several movements is subtle: the aria “Ich folge” expresses Peter’s promise to follow Jesus in his suffering—and yet the listener well knows that this promise is not kept. Later, Peter’s failure is made manifest when the same musical idea returns at the moment the “King of the Jews” is mocked by the crowds.

An interesting movement that demonstrates Bach’s skills as an interpreter of the biblical narrative is the chorus “Wir haben ein Gesetz” (We have a law); Bach expresses the concept of “law” by composing a strict fugue, in which one voice imitates the other following a clear and strict set of rules. In other words, the musical texture follows its own musical “law.”

Integral to the passion are numerous Protestant hymn settings, simple in style and similar to congregational singing. While the arias portray the meaning of the biblical narrative from the perspective of the individual, the hymns serve as reflection from the perspective of the entire congregation, a function that becomes obvious in the very first hymn setting of the passion. The biblical narrative reports the arrest of Jesus, ending with Christ’s words: “Ich habs euch gesagt, daß ichs sei, suchet ihr denn mich, so lasset diese gehen!” (I have told you I am the one; if you are looking for me, then let these others go!). The hypothetical congregation, represented by the choir, replies with the hymn stanza: “O große Lieb…” (O great love, o love beyond all measure, that has brought you on this path of torment! I lived with the world in delight and joy, and you have to suffer), emphasizing the responsibility of all humanity for the suffering of Christ.

The second half of Bach’s composition reports the trial of Jesus, his torture, crucifixion, and burial. It again is framed by two hymns, the first a simple four-part setting of “Christus, der uns selig macht” (Christ, who makes us blessed), whose words summarize Christ’s arrest and torment, thus bridging the gap between part one and part two of the passion, while the final movement is a setting of the hymn stanza “Ach Herr, lass dein lieb Engelein” (Lord God, let your dear angels).

One of the most dramatic movements in the work is the aria after the death of Jesus. The biblical narrative is followed by the aria “Es ist vollbracht” (It is accomplished) for alto and viola da gamba. The timbrally low and sonorous solo instrument, combining with descending musical lines in the solo vocal and instrumental parts, is evocative of the grief and despair after Jesus has expired.

However, no setting of the passion after the Gospel of John would be complete without a glimpse of Christ’s glory as well, the glory already foretold in the opening measures of the work. And indeed, in the middle section of “Es ist vollbracht,” Bach changes the character completely: the text portrays the victorious hero of Judah while the music displays exuberant fanfare-like motives, resembling trumpet calls of victory. Only at the very end does the music return briefly to the sadness of the beginning, a sadness already transformed by the short glimpse into the victory of Easter morning.

The passion ends with a double “finale.” After the burial, reported in a recitative, the choir sings an extensive setting of the text “Ruhe wohl.” The texture is simple, and the calm triple meter resembles a lullaby, set as a farewell to Jesus. But it is also a supplication that the “holy bones” that are buried in peace will, in turn, give peace to the believer. “Ruhe wohl” is followed by a quiet and simple setting of the hymn stanza “Ach Herr, lass dein lieb Engelein” (Lord God, let your dear angels), which widens the perspective from the death of Jesus to the death of the believer, and implores God to send his angels in the hour of the believer’s death, and bear the departing soul to the bosom of Abraham.

Markus Rathey

Associate Professor of Music History

Yale University