How a Yale Alum and New Haven Pastor Helped Bring Spirituals to Germany

Markus Rathey

When were the first African American spirituals sung in Germany? You can often read that American soldiers brought spirituals with them when they were stationed in Europe after World War II. And this is not entirely wrong: Military personnel stationed in Germany and the American radio networks were instrumental in bringing spirituals and other American music to the Old World. However, the story starts much earlier, and it involves a Yale alum.

Spirituals had been transmitted orally among enslaved people of African descent for a long time. Soon after the end of the Civil War, the songs found their way into print publications and on the concert stage. The public presence of spirituals was influenced especially by the efforts of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Established to raise funds for Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, the group started giving concerts first locally and then across the United States. The performances consisted almost exclusively of spirituals, often accompanied by a piano and in four-part settings. Already in 1873, the Jubilee Singers were invited to perform in England.

A second tour to Europe followed shortly thereafter. Once the Jubilee Singers finished performing in the Netherlands, they embarked in 1877 on an exhausting tour through Germany, where they sang in almost 100 cities. The programs included well-known spirituals such as “Go Down Moses” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and were attended by thousands of listeners. Not only were concert tickets for sale, but audiences could also buy a small book with the ensemble’s history, which included 104 of their songs in an appendix. This is the first time that Germans not only heard spirituals, but they were able to sing the songs at home. A German translation of the book was quickly finished and sold at the concerts as well. The translation did not include the sheet music for the songs, which were only to be found in the original version. However, the book opened with a new preface that set the tone for the German perception of the African American ensemble.

A second tour to Europe followed shortly thereafter. Once the Jubilee Singers finished performing in the Netherlands, they embarked in 1877 on an exhausting tour through Germany, where they sang in almost 100 cities. The programs included well-known spirituals such as “Go Down Moses” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and were attended by thousands of listeners. Not only were concert tickets for sale, but audiences could also buy a small book with the ensemble’s history, which included 104 of their songs in an appendix. This is the first time that Germans not only heard spirituals, but they were able to sing the songs at home. A German translation of the book was quickly finished and sold at the concerts as well. The translation did not include the sheet music for the songs, which were only to be found in the original version. However, the book opened with a new preface that set the tone for the German perception of the African American ensemble.

The preface was written by Revered Joseph Parrish Thompson (1819-1879), who can easily be called the most influential American in Berlin at that time. He had moved to Berlin in the early 1870s to advise the newly founded German state in questions of the relationship between church and state. His book Church and State in the United States: With an Appendix on the German Population, published in 1873, outlined a model for how the state should interact with the two major denominations of Protestantism and Catholicism and how the close relations between church and state, which had its roots in the Thirty Years’ War, could be refashioned in a more diverse and secularized society. Thompson was an adviser to Chancellor Otto von Bismarck and also held close contact with the circle of the German Emperor, Wilhelm I.

But what is more important for Thompson’s legacy is his involvement in the abolitionist movement in the US. As a congregationalist minister, he preached against slavery and published a harsh theological condemnation of dehumanizing practices in his early book The Fugitive Slave Law: Tried by the Old and New Testaments (1850). He remained an important voice in the theological fight against slavery and advised President Lincoln on numerous occasions.

Thompson’s successful career actually started in New Haven. He was a Yale student and graduated in 1838. He later continued his studies in Massachusetts at Andover Theological Seminary (now also part of YDS) and at Harvard. During his time in New Haven, Thompson served the congregation at Chapel Street Church (later known as “Church of the Redeemer”) from 1840 to 1845; and from 1845 to 1871, he was pastor at Broadway Tabernacle Church in Manhattan before embarking for Germany soon thereafter.

When the organizers of the Germany tour of the Jubilee Singers reached out to local supporters, Thompson was a natural choice: American, a leading theologian, and closely tied to the emancipation of formerly enslaved people in the US. When writing his preface for the German translation, which would then be sold at every concert and reach thousands of readers, he not only highlighted the religious significance of the spirituals, but he viewed the singers as a continuing reminder of the struggles of African Americans and the abolition of slavery. Differentiating the Jubilee Singers from the long practice of minstrel performances in blackface, Thompson writes in his preface: “These [singers] do not belong to the carnival performers who do their tricks and make jokes to entertain their audience. They must not be confused with the crowds of so-called ‘Minstrels,’ who are whites making fun at the expense of a race that deserves support and compassion. No, these are truly Christians who serve the most honorable cause of humanity: to give [former] slaves means and ways to benefit from their newly won freedom.”

Not only freedom for the enslaved but also dignity was what Thompson demanded. And this is the perspective from which he reports about the Germany tour to his American readers when he writes in the New York Independent about a Berlin recital, “The kindly, hearty approbation of such an audience was a certificate of character as well as of musical merit. They were received at the palace not as a strolling band of singers, but as ladies and gentlemen.”

The songs of the Jubilee Singers remained popular in Germany for decades. A German translation of 27 of the spirituals appeared in print in 1878 and it was reprinted numerous times until publication ceased with the 44th edition of the book in 1924.

The songs of the Jubilee Singers remained popular in Germany for decades. A German translation of 27 of the spirituals appeared in print in 1878 and it was reprinted numerous times until publication ceased with the 44th edition of the book in 1924.

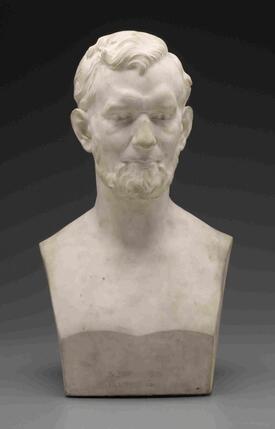

Thompson did not see the fruits of his support for the Jubilee Singers. He passed away in 1879, shortly after the ensemble had returned to the US. The Yale Art Gallery owns a marble bust of Thompson (not currently displayed), which was made in 1872, and pictured here.

Markus Rathey is the Robert S. Tangeman Professor of Music History

The essay draws on material from Prof. Rathey’s chapter “Spirituals Share the Stage with Mozart and Beethoven: The Germany Tour of the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1877/78 and the Responses of the German Press” in his new book Sacred and Secular Intersections in Music of the Long Nineteenth Century: Church, Stage, and Concert Hall, ed. by M. Rathey and E. Papanikolaou (Lanham: Lexington, 2022).