A fond reminiscence with Anne and Jeffery Rowthorn

by Clare Byrne, M.A.R. expected ‘22

What is the Yale Institute of Sacred Music? If you ask three people, you might get three different answers: a community that fosters religious inquiry through music and the arts; a cross-denominational training-ground of artists, ministers, and scholars; an experiment in interdisciplinary collaboration. It is all these things, and more.

How did this unique academic entity come to be? Who were the minds and energies behind this forty-seven-year-old endeavor, in a constant state of evolution? What would they think of the Institute today?

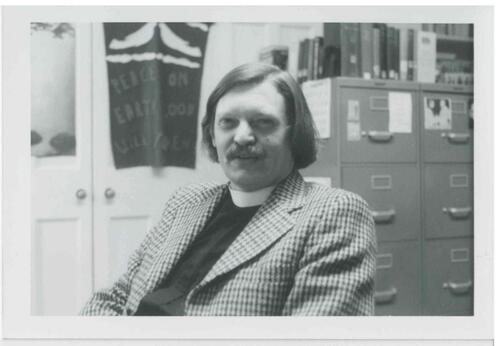

One of those minds belongs to the Right Reverend Jeffery Rowthorn, professor of worship and one of the three founding faculty members of the ISM. He and his wife, Anne, chatted with me recently over Zoom from their home in Salem, CT.

The story began in 1973 in New York City. As the Vietnam War drew to a close, the Watergate scandal brought a president to his resignation, the Supreme Court ruled on Roe vs. Wade, and the World Trade Center opened in a ribbon-cutting ceremony. Robert Baker was the beloved dean of the School of Sacred Music at Union Theological Seminary (UTS) on the Upper West Side, a conservatory devoted to the training of church musicians, principally organists. It was Baker, professor of sacred music and himself an eminent organist, who would take the first steps in creating the Institute of Sacred Music and then in shaping it as its first director.

In 1973, Rowthorn, originally from Wales, had been at Union for five years as its first liturgical chaplain, and later as dean of instruction. He was still a junior faculty member, “a kid professor, really,” as Anne put it. She was then in graduate school at Columbia and later NYU. The couple had three small children and were as settled as a young family could be.

In 1973, Rowthorn, originally from Wales, had been at Union for five years as its first liturgical chaplain, and later as dean of instruction. He was still a junior faculty member, “a kid professor, really,” as Anne put it. She was then in graduate school at Columbia and later NYU. The couple had three small children and were as settled as a young family could be.

As in many beginnings, the Institute was born out of a crisis. UTS, like the nation at large, was in a state of social and financial upheaval. Its Board of Directors was looking for ways to trim the budget. The School of Sacred Music, a well-established institution of forty-five years within Union Seminary, with approximately fifty students and six fulltime faculty, was nonetheless financially vulnerable. Just how vulnerable became evident when the School of Sacred Music was cut from the budget.

It was a heartbreaking moment for its faculty, students, and alumni. The Rowthorns well remember how many junior faculty at UTS faced painful uncertainty and job cuts; some faculty were actively being encouraged to pursue other teaching opportunities.

The Rowthorns had formed strong collegial friendships with the faculty and staff of the School of Sacred Music through ongoing collaboration in worship and study. Jeffery prepared daily worship for chapel with students at the School of Music. As he tells it, he had an office next door to the Music School, where he’d often stop by for morning coffee and chapel planning. On Fridays there was a standing TGIF party, replete with hors d’oeuvres and aperitifs. Other gatherings were planned “at the least provocation,” Jeffery said.

Robert Baker was close friends with Clementine Tangeman, known to her friends as Clemmie. She was the widow of Robert Tangeman, a musicologist at the School of Sacred Music who had died in 1964. Baker was also friends with her brother, J. Irwin Miller, and his wife Xenia. Tangeman and Miller were the sibling heirs to the Cummins Engine Company fortune. They established the Miller Foundation to further their many philanthropic interests. Largely due to the Miller family, Columbus, Indiana is a living museum of works by the nation’s leading architects, including I. M. Pei, Eero Saarinen and others.

The Miller family was deeply interested in supporting sacred music. Mrs. Tangeman had edited a hymnal for the Disciples of Christ, and Irwin Miller had attended Yale and was a prominent member of the Yale Corporation. They wanted to make a contribution that would last. The idea came to Robert Baker that perhaps the Miller family would be interested in funding a new institute of sacred music at Yale. Baker got in his car and drove straight for thirty-six hours to Columbus to propose this to Clemmie. She immediately warmed to the proposal and shared it with her family. In due course Baker’s vision was accepted by the Miller Foundation, and

Clemmie wrote the founding document that accompanied the grant.

Thus as the School of Sacred Music prepared to close its doors, a fledgling Institute of Sacred Music was conceived for New Haven, Connecticut. What was envisioned was an expanded, integrated academic and artistic community that would partner closely with Yale Divinity School and the Yale School of Music, but be financially independent. It would have room to expand, with a core mission of artistic and scholarly collaboration.

The original endowment of the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale was ten million dollars, and Baker was appointed director. Jeffery says he remembers sitting in a Union classroom when Bob asked him, “Would you like to come to Yale with us?”

“The offer was a godsend,” Jeffery said. It answered many uncertainties in the tumult at Union. Rowthorn eagerly accepted a joint appointment to teach worship at Yale Divinity School, Berkeley Divinity School, and the brand-new ISM. The other faculty member to make the pilgrimage from Union to Yale was the music historian Richard French.

The dismantling, re-assembly, and re-invention of an entire school from New York City to New Haven was a tremendous logistical feat. Into that task stepped Mina Belle Packer, the unflappable administrator of the School of Sacred Music, who took matters in hand to engineer its rebirth as the Institute of Sacred Music. A graduate of the School, a planning genius, and a tall, commanding presence, Packer was not one to trifle with.

“She did everything.” Jeffery recalled. “The faculty would chart the basic direction of the new institute and Mina Belle would add legs to our ideas.”

The shape of the Institute today has much to do with how the original faculty stepped into their roles. While Robert Baker’s focus in music was broad but traditional, Jeffery Rowthorn and Richard French were eager to explore progressive directions in worship and music. They saw the creation of the Institute as a chance to throw open the doors, “an opportunity for us to be bolder,” Jeffery said. The first class they co-taught at Yale was a seminar called Contemporary Worship. Rowthorn said of French, “He was very excited about getting people like Alexander Schmemann, the Orthodox theologian from St. Vladimir’s Seminary. That made a statement,” Jeffery added. “I didn’t realize its significance until later, but the first course that we offered was interdisciplinary.”

The first ISM class arrived in September 1974, a class of ten students. As their names were read, Anne and Jeffery remembered each member of that initial class distinctly and fondly, and many lifelong friendships were formed in those early days. Clementine Tangeman continued to take a lively interest in the Institute and she visited frequently. “She would come into town on the company jet … fly into Tweed New Haven Airport, and Jeffery being the junior boy on the faculty, would drive out on the tarmac and pick her up from her plane,” Anne said.

Jeffery created opportunities for students to take a primary role in planning worship in Marquand Chapel. The new format gathered students – two from the Divinity School, and two from ISM – to collaborate on daily worship planning. Mondays and Thursdays were preaching services, Tuesday was sung Morning Prayer, Wednesday was devoted to experimental worship and Friday was an ecumenical Eucharist. We made a real effort to bring everybody together in this ecumenical worship—the Institute, the Divinity School and Berkeley. In 1980 Jeffery and students Bruce Neswick (M.M. ’81) and Thomas Jones edited and published, Laudamus, a new hymnal for use in Marquand Chapel. “With the creation of ISM’s three singing groups—the Camerata, the Schola Cantorum and later the Voxtet, the Institute has made a significant cultural contribution both to Yale and to the larger New Haven community. We were in effect saying, “This is what we can give; this is who we are.”

Looking at its evolution, he added, “I think what has always impressed us is the way in which the Institute has celebrated its growth, taking seriously every new person coming in and bringing fresh possibilities with them.”

The Rowthorns left ISM and YDS in 1987 when Jeffery was elected Bishop Suffragan of the Episcopal Church in Connecticut; later he was Bishop of the Episcopal churches in Europe. But as Jeffery and Anne tell it, in a sense they never really left. “One of the things that has blessed us greatly is that even though we moved on in terms of responsibilities, we have continued to be part of the Institute. Martin Jean, in particular, and everyone currently at the Institute have made us hugely welcome.”

The Rowthorns left ISM and YDS in 1987 when Jeffery was elected Bishop Suffragan of the Episcopal Church in Connecticut; later he was Bishop of the Episcopal churches in Europe. But as Jeffery and Anne tell it, in a sense they never really left. “One of the things that has blessed us greatly is that even though we moved on in terms of responsibilities, we have continued to be part of the Institute. Martin Jean, in particular, and everyone currently at the Institute have made us hugely welcome.”

Anne added, “I don’t think Bob Baker could have imagined what the Institute would eventually become; it just keeps getting better and better. It has decisively enriched the musical culture of the City of New Haven and beyond. The whole explosion into the range of the arts was completely new at the time. Its growth in every area has been spectacular. Furthermore, the quality of the students with their multitude of talents is breathtaking.”

“Looking back over almost half a century,” the Rowthorns write, “we are reminded of the importance of friendships and the power of inspired innovation and bold creativity. Together they have forged the first chapters of a story that continues to have ripple effects which none of us could have begun to imagine when we first set out on this adventure.”

_____

The Rowthorns at the dedication of Miller Hall, February 2019. Photo by Tony Fiorino

Lead photo of the Rowthorns today by William McKeown