Ed. Note Again this year, during spring break a merry band of pilgrim/scholars embarked on an extended field trip in connection with a class taught by ISM faculty. Thirteen students and one staff member joined Professors Markus Rathey and Bruce Gordon on a trip to Germany for in-depth exploration of themes from the class “The German Mystical Tradition in Theology, Piety, and Music,” which focused on expressions of mystical religion in the extraordinarily rich tradition of Christian mysticism flourishing in German lands between the eleventh and eighteenth centuries. Stops on the weeklong trip included Mainz, Rüdesheim, Berncastel-Cues, Wiesbaden, Erfurt, and Frankfurt.

Postcards from Spring Break 2015

compiled and edited by Joanna Murdoch (M.A.R. ‘15)

Photos by Martha Brundage, Emilie Coakley, Joanna Murdoch, Wyatt Smith, and Jonathan White

Martha H. Brundage (M.A.R. ‘15)

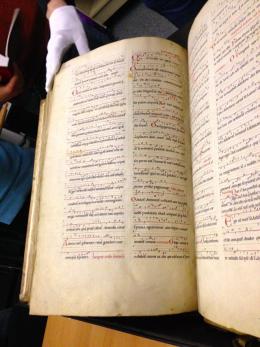

The library of the RheinMain University of Applied Sciences in Wiesbaden, a university founded in 1971, is one of the last places I would have imagined finding the Riesencodex, a giant “collected works” manuscript attributed to the twelfth-century German Benedictine polymath Hildegard of Bingen. The Codex was thrilling to see, as it is the definitive edition of Hildegard’s visionary writings alongside her complete musical works. While spending time with such a theologically and musically important manuscript would have been inspiring in and of itself, the afternoon exceeded

The Riesencodex has lived many lives, and through it, so has Hildegard. Handwritten by six scribes in Hildegard’s monastery in Rupertsberg, it remained in the convent for centuries as a theological and musical resource. During the Thirty Years’ War, Swedish troops looted the monastery, and the Codex was ferried across the Rhine to a sister monastery in Eibingen for safekeeping. In 1814, after the founding of a state library in Wiesbaden, the manuscript found a home within its collections.

This riveting story brought the manuscript to life. It borders on the miraculous that we still have access to this manuscript, from which we derive the modern translations we read in class and what knowledge we have of Hildegard’s visionary activity. Whether or not one agrees with her mystical theology, the fact that Hildegard’s work has survived so many catastrophes is cause enough for me to read it carefully and thank God for the education available to me today.

Emilie Coakley (M.A.R. ‘15)

Unity in diversity. This seemingly simple refrain made absolutely no sense to me as I sat in the ISM seminar room in late February, trying to wrap my brain around Nicholas of Cusa’s paradoxical statement about the unity of the Trinity. Ever the doubting Thomas, I wondered if our upcoming class trip to Germany and visit to Berkastel-Kues, the birthplace of the fifteenth century philosopher, theologian, jurist, and astronomer, would help me see and feel what I was missing. I found myself, weeks later, standing in the courtyard of the Cusanusstift—the library and retirement home where Nicholas had hoped to live out his final days—surrounded by the concrete manifestation of his ideas. From the middle of the courtyard, I noticed intricately crafted windows, all of a similar shape and strikingly rimmed in terracotta stone. Unity. And yet, on closer examination, each was just a little bit different from the others, the patterns playing out in the triangle upper portion of each three-pained panel not exactly the same as those around it. Diversity. I finally got it. Driving home Nicholas’s genius, each wall was graced with a different number of windows.  The portals shared their illuminating function but allowed different amounts and patterns of light into each of the stone-floored hallways. Unity in diversity had finally become real to me, etched into wood and stone in the seamless symbolism that Nicholas of Cusa employed in his theological writings. [Above: The inner courtyard windows in Nicholas of Cusa’s retirement home, a model of unity in diversity.]

The portals shared their illuminating function but allowed different amounts and patterns of light into each of the stone-floored hallways. Unity in diversity had finally become real to me, etched into wood and stone in the seamless symbolism that Nicholas of Cusa employed in his theological writings. [Above: The inner courtyard windows in Nicholas of Cusa’s retirement home, a model of unity in diversity.]

Leaving the illuminating courtyard, we marched up a glass-enclosed spiral staircase to encounter a different sort of enlightenment bound in books. Volumes of medieval philosophy and theology revealed what Nicholas considered important enough to read, and what later rectors valued enough to purchase even after his death. A thirteenth-century manuscript of Hildegard’s vision collection Scivias was on hand, alongside a copy of works of Meister Eckhart, with Cusa’s marginalia gracing its borders. Seeing how the ideas of these Rhineland mystics traveled up and down the  Rhine River, realized on pages and shared across stretches of time and space, was mind-boggling. Unity in diversity was not just a theory for Nicholas of Cusa; it was his life. And his legacy continues: today, a community of around sixty men and women still live in the foundation he established, despite centuries of secularization and war. [At right: ISM administrator Kristen Forman pauses to admire the entrance to Nicholas of Cusa’s library]

Rhine River, realized on pages and shared across stretches of time and space, was mind-boggling. Unity in diversity was not just a theory for Nicholas of Cusa; it was his life. And his legacy continues: today, a community of around sixty men and women still live in the foundation he established, despite centuries of secularization and war. [At right: ISM administrator Kristen Forman pauses to admire the entrance to Nicholas of Cusa’s library]

Through a small stone-cut window in the library’s west wall, we gazed at the chapel below, where Nicholas’s heart had been buried as he requested. His body is interred in Rome, but his heart rests in the shadow of this altar, in the place he had hoped to call home.

Patrick Kreeger (M.M.’15)

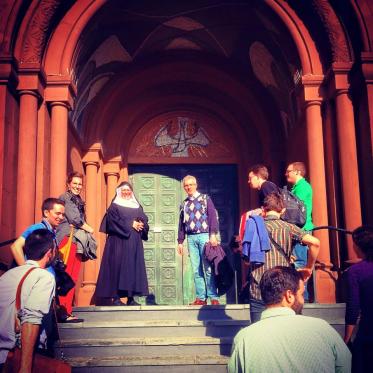

Reflecting on our class trip to Germany, many new memories and experiences come to mind. The food, the culture, the discussions—all enriched our study of German mysticism in theology, piety, and music. In particular, I was impressed with our visit to Eibingen Abbey on the banks of the Rhine River. A forty-five-minute walk up a steep hill, this abbey celebrates the German mystic Hildegard of Bingen. We met with a nun at the entrance. She gave us a detailed history of her time at the abbey, as well as the story of the abbey itself. I was amazed to see the artwork in the sanctuary during our tour; it reminded me of the 2014 ISM study tour in Italy, when we visited Ravenna’s Basilica of San Vitale and admired its breathtaking mosaic program. Although Eibingen Abbey had no mosaics, the walls and ceilings in the chapel were similarly elaborate in depiction, displaying three levels of narration: Bible stories, saints’ lives, and the life of Hildegard herself. These ornate pictures served a purpose greater than decoration, perhaps illustrating Christian stories for illiterate medieval visitors—perhaps even anticipating the impulse we saw in our course readings

Reflecting on our class trip to Germany, many new memories and experiences come to mind. The food, the culture, the discussions—all enriched our study of German mysticism in theology, piety, and music. In particular, I was impressed with our visit to Eibingen Abbey on the banks of the Rhine River. A forty-five-minute walk up a steep hill, this abbey celebrates the German mystic Hildegard of Bingen. We met with a nun at the entrance. She gave us a detailed history of her time at the abbey, as well as the story of the abbey itself. I was amazed to see the artwork in the sanctuary during our tour; it reminded me of the 2014 ISM study tour in Italy, when we visited Ravenna’s Basilica of San Vitale and admired its breathtaking mosaic program. Although Eibingen Abbey had no mosaics, the walls and ceilings in the chapel were similarly elaborate in depiction, displaying three levels of narration: Bible stories, saints’ lives, and the life of Hildegard herself. These ornate pictures served a purpose greater than decoration, perhaps illustrating Christian stories for illiterate medieval visitors—perhaps even anticipating the impulse we saw in our course readings

Wyatt Smith (M.M. ‘15)

Over the course of our one-week trip in Germany, two figures stood out to me from the other mystics: the twelfth-century abbess, theologian, and composer Hildegard of Bingen; and Martin Luther, the sixteenth-century Protestant reformer.

Hildegard’s work was a recurrent theme throughout the week, as portions of three separate days were devoted to her. Visiting her Benedictine abbey at Eibingen provided a unique view into her life, reminding us that Hildegard was not a primarily a mystic, but rather the abbess of a Benedictine order. This aspect of her life is often overshadowed

Two days later came one of the true highlights of the trip: Seeing Hildegard’s Riesencodex. The knowledgeable librarian Martin Mayer spoke both of the formation of this large volume and its journey through the ages. We were able to request to see different parts of the book, including the last portion of the book, which contains Hildegard’s musical compositions. The pages containing Hildegard’s music appear well worn, suggesting frequent use before being filed in the Riesencodex.

[Left: Afternoon sun warms the façade of the twentieth-century chapel at Hildegard’s abbey in Eibingen]

Toward the end of our trip, we heard a Hildegard lecture by music and theology scholar Dr. Barbara Stühlmeyer. What resonated most with me was the manner in which she had studied and absorbed the music of Hildegard: living the day-to-day life of a Benedictine nun, Dr. Stühlmeyer had been able to immerse herself, body and soul, in Hildegard’s spiritual and musical milieu, singing Hildegard’s many songs in the context of the Divine Office. This methodological approach—an attempt to live the life for which the music was intended—reminded me of my own experiences blending study, music, and devotional experience here at Yale. For my third degree recital, I prepared and performed Johann Sebastian Bach’s six large chorale preludes on the catechism hymns of Martin Luther from Klavierübung III. At that time I was also taking a course entitled “Theology of the Lutheran Confessions” at Yale Divinity School, which further solidified my theological foundation as a Confessional Lutheran.

All in all, this trip was fulfilling both academically and personally. Many concepts from the class, which otherwise would have remained in the ether of my mind, have now been contextualized by way of this trip. I will be forever grateful to the ISM for providing this opportunity to study in Germany for a short while!

[Above: Studying key works of 16th–18th century theology in the Lutheran library at the Augustinerkloster: Profs. Markus Rathey and Bruce Gordon, left, and Adam Perez (M.A.R., Religion & Music) and Patrick Kreeger, right]