A Word about the Tradition

Allowing Suffering to Speak: Black Gospel’s Transfiguration of Sorrow into Song

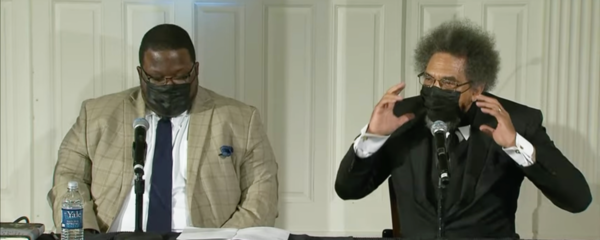

During the program’s inaugural event, one of our special guests, Professor Cornel West, spoke at length about the origins and meanings of the Black gospel tradition. Over and over again, Professor West used words like “cultivate” and “transfigure” to describe the relationship between the power of Black sacred music and the centuries of struggle from which this tradition arises. West recalled that this music descends from the “guttural cries and wrenching moans and visceral groans of our brothers and sisters in those slave ships.” As he tuned into the resonance of those who labored on plantations, as well as that of “share croppers and tenant farmers and inhabitants of the ghettoes and the hoods,” Professor West argued that Black gospel, in both form and content, is a method of conveying truth. This insistence echoes the pioneering liberation theologian James Cone’s assertion that “the truth of black religion is not limited to the literal meaning of the words. Truth is also disclosed in the movement of the language and the passion created when a song is sung in the right pitch and tonal quality. Truth is found in shout, hum, and moan as these expressions move the people closer to the source of their being” (God of the Oppressed 1975, 21).

As Professor West powerfully argued that night, the condition of truth is allowing suffering to speak. Instead of entertainment, and working against mere “stimulation and titillation,” Black gospel reaches its audiences with depth, profundity, ethics, and love. Armed with this context, it was clear to those in Marquand–and to the many who watched online–that the extraordinary musical skill of Wolfock, Jackson, Hill, and Davis indexes not only individual creativity, but also each individual’s recognition of their place within a tradition that transcends generations. Even though COVID-19 made it impossible to sing in any conventional sense, each instrumentalist sang in a different way. Every note they played forged a deeper connection between their audiences and the work song, the spiritual, the hymn, the gospel song, and the numerous other streams of Black sacred music.

Given the evening’s special status as the inaugural event of the Program in Music and the Black Church, Professor West’s argument was, in a sense, the first “word about the tradition.” The wisdom he shared teaches that the sacred is always political, and that the politics of this tradition are intimately associated with the pursuit of freedom and justice. These politics take sonic form in the full range of performances whose combination of beauty and passion, joy and the evidence of suffering, yield a distinctive kind of affect, intensity, and power.

This video excerpt includes even more of Professor West’s impassioned articulation of the Black gospel tradition. You can also watch the entire inaugural event.