The Yale Institute of Sacred Music is unique in all the world because of circumstances that led to its founding in 1973, because of the broad mission set out by its benefactors, and because of its home within one of the world’s great research universities.

Over the past five decades, the ISM has grown from a group of three faculty and ten students to a community of over 120 staff, faculty, students, and visiting scholars and artists. In addition to our longtime partnerships with the Yale School of Music and Yale Divinity School, our work now extends to the departments of American Studies, Art History, Medieval Studies, Music, Religious Studies, as well as to various university collections and galleries. While most of our work remains grounded in Christian studies, a growing amount extends to music, ritual, and related arts of other religious traditions.

The founding personnel of the ISM migrated to Yale from the School of Sacred Music at Union Theological Seminary (UTS) in New York City, a preeminent American ecumenical seminary. Begun in 1928, the School was the idea of UTS president Henry Sloane Coffin and Drs. Clarence and Helen Dickinson, in order to offer the highest caliber of training to church musicians within the context of a theological school. Clarence Dickinson was its first director, followed by Hugh Porter in 1945, and in turn succeeded by Robert S. Baker in 1962.

In many ways, the School of Sacred Music at UTS was a natural consequence of the revival of sacred music that had swept through nineteenth-century Europe through the Oxford and Ecclesiological Movements, the chant revival at Solesmes, and the Cecilian movement in central and southern Europe. Students in the School numbered, on average, about 60 at any one time and received rigorous training in organ and service playing, choral conducting, singing, and composition. Their academic work included music history, liturgical studies, and theology. Graduates of the program went on to teach and to lead music in some of the great cathedrals and churches throughout North America and beyond, instilling a new appreciation for the classic repertoire of hymnody, chant, and choral music as situated in historic rites and architectural environments.

However, this noble enterprise was not to survive the turmoil of the late 1960’s. By 1970 Union Seminary was in financial crisis, and in 1972, the School was closed. Undaunted, Robert Baker applied for a major grant from the Irwin-Sweeney-Miller foundation of Columbus, Indiana. This family foundation was led by Clementine Miller Tangeman (whose late husband had taught music history for years at Union), and by her brother, J. Irwin Miller, then on the corporation of Yale University. They were both leaders in the Disciples of Christ church, having supported seminary and musical education in the denomination for years. They had long contemplated beginning a venture at Yale similar to the Union School, and so in May, 1973, they awarded a grant of $10 million to Yale University to establish an Institute of Sacred Music here.

In the grant letter to the university, they wrote: “First, out of what context does our interest in an Institute of Worship, Music, and the Related Arts arise? It rises out of our concern for the needs of the spirit among people living today; out of our own Christian convictions; and out of our belief in the importance of the arts (especially music) as valid and compelling means of transmitting to men and women the essence of the Christian Gospel.” They hoped for fruitful partnerships with Yale’s Divinity School and School of Music to be sure, and also with Yale College, the Graduate School, the Schools of Art, Architecture, the Chaplain’s office, and the museums—indeed, with the whole university.

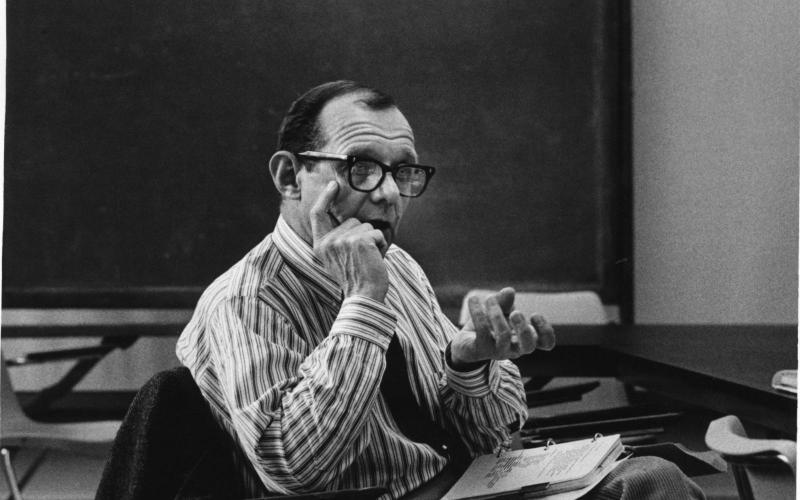

Robert Stevens Baker became the first director of the ISM and had the daunting task of establishing the Institute at Yale. He was joined by three colleagues from Union: Richard French (music history), Jeffery Rowthorn (worship), and Mina Belle Packer Wichmann (administrator). Mina Belle Wichmann recalls, “By September 1974 we had produced a curriculum, restructured the former gym at Yale Divinity School to include classrooms, office space, and practice rooms; purchased several Steinway grand pianos, contracted for four studio and practice pipe organs; advertised for students, and accepted ten graduate applicants for Yale School of Music and Yale Divinity School (five each), who shared our visions for this new enterprise, the Yale Institute of Sacred Music.”

Upon Baker’s retirement in 1976, the conductor Jon Bailey was director from 1976 to 1982 and continued the initial trajectory of making the ISM one of the premier centers for the study of church music and worship. The student body and faculty, which grew steadily during this period, increased energy and quality in sacred music performance around Yale and especially in Yale’s chapels, and graduates from this period still hold major posts in the church and the academy today.

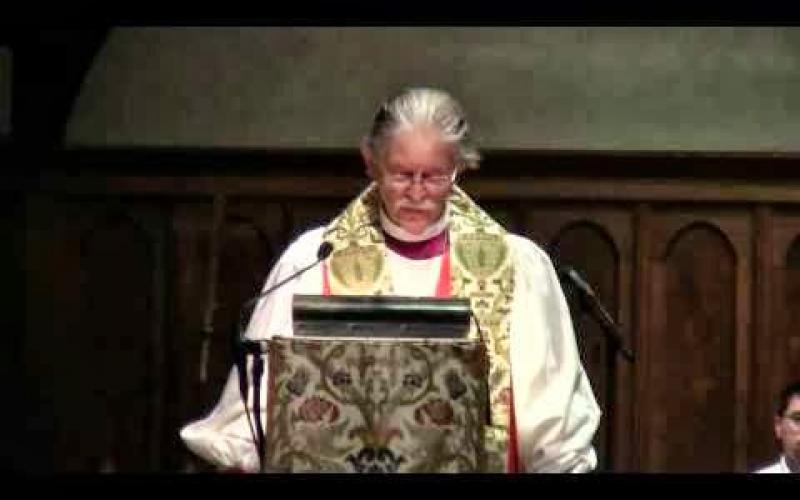

John Cook was named director in 1984 (after an interregnum of two years). Already on the Yale Divinity School faculty, he added the existing religion and arts program to the Institute’s portfolio. The Yale Camerata was formed in 1985. A redesign of the ISM’s curriculum led to even more integrated learning among the students, and a dual degree program was introduced allowing students to pursue both a divinity and a music degree together. Capturing major grants from the Lilly and Luce Foundations, the Institute led the way in making the arts an integral part of theological education. International conferences were convened around broad themes such as “Jerusalem,” “Imagining Mortality,” and “Utopia.” Cook’s famous study trips abroad were built upon, and are still part of, the ISM’s offerings today.

When John Cook was recruited to be president of the Luce Foundation in 1992, the university searched for his replacement for two years. These were indeed transition years for Yale, as President Benno Schmidt also stepped down from office in 1992. Then Richard Levin, one year into his presidency, appointed the charismatic medieval music historian Margot Fassler, who held the ISM director post through 2004.

The student body increased again during this period from forty to sixty-five. The ISM’s public programming flourished mightily and continues to include literary readings, art exhibitions, lecture series, and conferences on various topics, as well as musical performances. The ISM began appointing a fellow in ethnomusicology each year. The worship program in Marquand chapel blossomed in new and innovative ways, and this in turn energized other campus ministries at Yale. In 2003, Yale Schola Cantorum was founded along with a new program for vocal graduate majors in 2004. When Margot Fassler stepped down as director, Levin wrote: “Margot was one of my first senior administrative appointees and one of the most successful. Her ten years of service to the Institute have been nothing less than spectacular.”

When Martin Jean moved into the director’s role in 2005, it was natural to keep on this energetic trajectory. The faculty renewed their focus on an integrated curriculum and formalized a course of studies in church music. Two new faculty lines in religion and the arts were added, and the single fellowship in ethnomusicology was expanded to six fellowships spanning all the Institute’s disciplines, to engage potentially with any religious tradition through the breadth of the Institute’s mission. Expanded outreach through exhibitions, special guest artists, scholarly gatherings, and summer offerings put even more people in touch with the Institute’s work, and through Schola tours and study trips, faculty and students have traveled to over a dozen countries on three continents.

In forty years, the work of the Institute has expanded and become ever more complex. However, through all of this change and growth, we hold dear the core concern for the work of religious communities in today’s world. We give thanks for the vision and gift that created the Yale Institute of Sacred Music, and we pray that our programs in music, worship, and the arts continue to serve the public in innovative and continually evolving ways.