When Ideas Find a New Home

Traveling to the United Kingdom for Professors Gordon and Rogers’ course Religion and Literature in Early Modern Britain felt something like a homecoming: Each student in the class already had an individual connection to the places we studied and lived. I think we were each seeking a different part of our individual stories and questions when we landed at London Heathrow that sunny March morning.

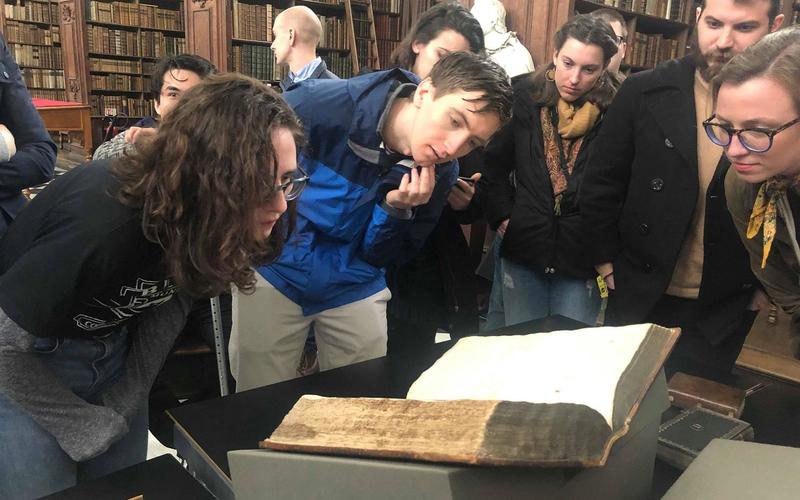

Of course, I can’t speak for any other student in the class, but from my understanding, we as scholars were first seeking answers to academic questions. Or, perhaps, more of a sense-based understanding of the environments in which our questions thrive. Some wanted to visit Westminster Abbey, perhaps to hear the great organ or see the graves of literary giants we admire so much. Others were fascinated by Foxe’s Book of Martyrs at the Wren Library and still others awaited with anticipation the visit to John Knox’s house in Edinburgh, Scotland.

In my estimation, the best aspect of the trip was continually seeing great minds come together to produce beautiful and innovative ideas, ideas that seemed groundbreaking and exciting in their own right. For me personally, the highlight of the trip was an afternoon spent in the office—or rather something more like a magical think tank—of Dr. Sophie Read, lecturer in English at Christ College, Cambridge.

Our class, something like an awkward and loving family at this point, ambled up narrow steps to reach Dr. Read’s office. We were greeted by the warmth of flower-decorated furniture and shining, shining sunlight. The large, open windows overlooking the gardens of Christ College let in the smells of freshly cut grass and roses blooming in the tenderly cared-for ground.

Dr. Read invited us into a conversation, into a kind of intellectual home. And there we sat talking about poetry and smells. Yes, smells. From the time of the Renaissance through the seventeenth century, the sense of smell played an important role in religious devotion, particularly religious devotional poetry. Think of the key role that incense has played in many parts of the Western Church for over a thousand years. Dr. Read presented us with ideas about embodied smell in religious devotional poetry.

Dr. Read lit a bit of frankincense in an incense burner on a table in the middle of the room. As we discussed devotional poetry and the power of smell, the scent of the frankincense wafted throughout the room, catching us at random in our thoughts. We discussed the ways in which George Herbert referred to the smell of “amber-greese” (ambergris), a scent produced by collecting the digestive juices of sperm whales, to signal a special relationship with God. Dr. Read passed around an Italian ambergris-based perfume so we could experience the meaning of the poem in a new way. Some of us inhaled deeply, enjoying the strong spiciness of the perfume. Others of us turned away in disgust.

This is true learning! I thought. The poem took on a newly complex meaning. And so did our experience: We grew into the history of the poem, understanding the new smell that accompanied it. We grew in relationship with each other, understanding how our own various reactions to a single scent embodied the complexity of the liturgical and theological questions we pursue in the history and literature of times past.

As I said, our class exploration of the United Kingdom was a bit like coming home—a home in which we found new meanings and new versions of the past we study and the selves we seek to understand. It was true learning, in the complete sense of the word: learning that matters, learning that changes, and learning that brings those who pursue it closer together.